I have been visiting my people in the USA these past couple weeks. While there I was invited to share with a family friend the story behind my daughter's name, a story which goes like this:

When I was growing up, one of my favourite television shows was Masterpiece Theater. A staple programme on PBS (the Public Broadcasting Service) it featured different imported series that had been produced and aired in the UK. In 1982 it showed The Flame Trees of Thika, starring Hayley Mills, David Robb and Holly Aird. Based on a memoir by Elspeth Huxley, The Flame Trees of Thika tells the story of her childhood in British colonial East Africa in the years before World War I.

Around this time, I bought a tie-in copy of the memoir: a Penguin paperback with smooth, soft pages which particularly appealed to me. Huxley wrote with an intelligent, insightful narrative voice and a subtle sense of humour, about her family's move to Kenya and their travails at coffee farming. I loved the accounts of the animals in her life: a pair of chameleons named Richard and Mary; a white pony named Moyale; and a duiker (small antelope) named Twinkle.

As an adult, Huxley held a respectable career as a writer and broadcaster, at a time when these fields were the domain of men. She wrote biographies, mysteries, assorted nonfiction and memoirs, as well as journalism about British international affairs and a variety of other topics. Again: her intelligence shone through her fine prose and she wrote with a reflective and compassionate perspective. I admired her for these qualities, and at the same time I fell in love with her name: Elspeth. I don't know why it held me so fast, but it became a beloved name which I promised myself I would christen a daughter should I ever have one.

However. And it's a big weighty thing, this however. Elspeth Huxley wrote from a benevolent colonialist perspective: it may have been benevolent, but it was still very much colonialist. Aaron Bady captures the essence of the difficulty here:

These books do a lot of things, I think, but a certain kind of historical amnesia is the thread that runs through all of them, each a different kind of evasion, a different way of un-telling the story she needs to keep not-telling, over and over again, the story of how white people stole Kenya from the Kenyans.... She was (and in some ways remains) the supreme apologist for settler colonialism, the official chronicler and storyteller whose work was to make it seem like a not-terrible thing to do.

When I was thirteen years old - watching and reading The Flame Trees of Thika from a prosperous white suburb in Chicago – I was oblivious to the cultural and racial indoctrination in which I swam. Forty-three years later, I must look at it square in the eye. It creates a painful realisation: that my childhood hero was flawed, my own personal limitations are significant and my learning must be paid for with effort and self-scrutiny. I'm reminded of James Baldwin's famous observation: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

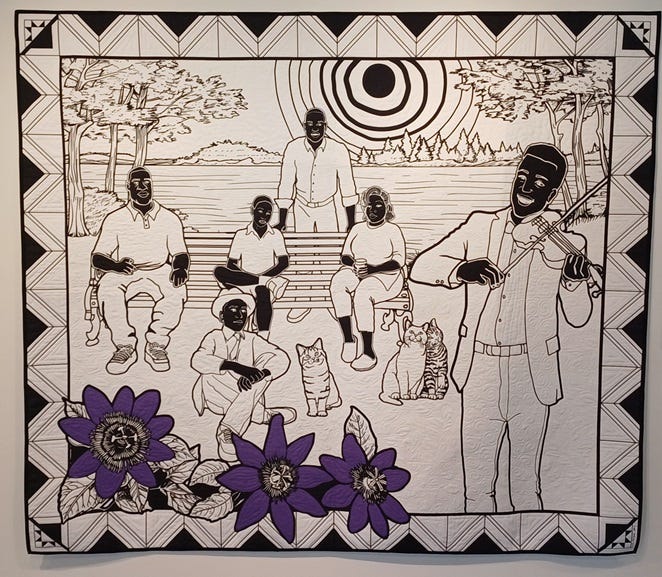

There is so much to face and so much to change. While in Minneapolis a friend took me to visit the Textile Center (https://textilecentermn.org/), where an exhibit of quilts by Carolyn Mazloomi featured. These striking black and white artisan quilts told episodes of Black American history and profiled Black American heroes and activists. We also drove through George Floyd Square, the intersection of streets where in 2020 a black man named George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer holding him down by the neck – a travesty which sparked massive riots around the city and paved the way for the Black Lives Matter movement.

The photo above shows Mazloomi's quilt memorialising the victims of racially-motivated murders. Don't be fooled by the small handful of individuals pictured (Elijah McClain, Emmitt Till, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, George Stinney and Breonna Taylor.) These few have become symbols of racial injustice, but they represent the myriad people who have died because of the colour of their skin.

Earlier in my trip, my brother took me to the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit where we viewed an exhibit called Code Switch (https://mocadetroit.org/code-switch/). The exhibit included a short film about state-sanctioned violence and its final credits listed all the names of Black Americans who have been killed by police in the United States since 2015. The list scrolled down... and down... and on and on. Hundreds of names, in the last decade alone.

How on earth do I end this post? My childhood hero and daughter's namesake was an apologist for white supremacy and colonial exploitation. No matter how sympathetic she was to her neighbouring Kenyans or informed about East African politics or curious about native culture – she participated in and represented a dominating force of racist violence, which across the globe has been responsible for countless deaths and unquantifiable suffering. British imperialism fuelled the settler colonialism which overtook both North America and East Africa, not to mention all the other areas of the British Commonwealth, the repercussions of which we see to this day.

Indeed: how do I end this post? In shame, sorrow and a renewed commitment to educate myself about racism and about how I can be an ally. And here is where my thoughts lead me: to a new friend in Chicago, whose Center for Mad Culture (https://www.madculture.org/) has inspired me to follow his footsteps and set up a similar entity here in the UK (a project still in its earliest manifestation.) Matt's motivation in setting up CMC, he explained to me, was the George Floyd murder and the subsequent activism which erupted in its wake.

As he explained it: one may best offer allyship, and contribute to progressive change in this world, by aligning with one's own lived experience and working for one's vision of a just, compassionate and peaceful world. I agree with this. We must draw on our own authority and our most honest and heartfelt understanding, when we engage with changemaking. Together we contribute and together we weave our threads into a shared social fabric.

I start from where I am. My recent travels have broadened my mind, galvanised my heart and left me with this: there is work to be done.

People are mimetic.

Forgive them for they know not what they do.

They, we, us, are made ‘up’ with the ingredients.

As of travel, the tour guide is our educational systemic problem.

A bipolarity, a double bind and confident.

The search is individualism, the words incorporate, the harm is speed.

The fixing or discovery is the theft.