Soul Manifestos introduction

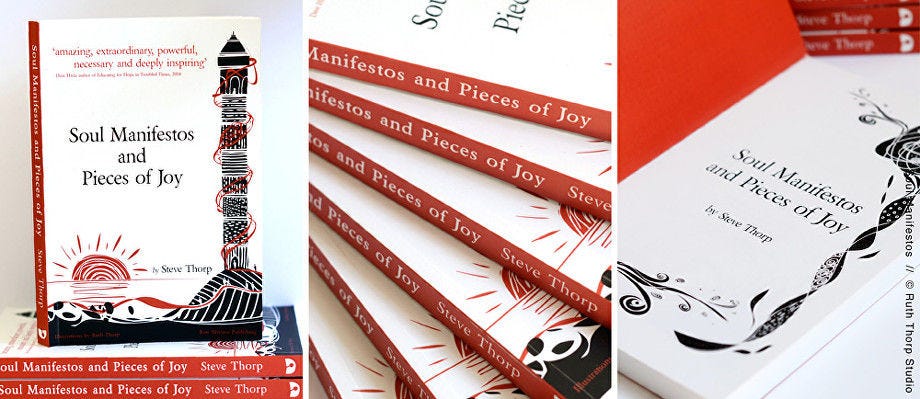

In 2014, I published a book of short poetic essays, Soul Manifestos and Pieces of Joy1. The book, illustrated by my longtime collaborator (and daughter) Ruth Thorp, is currently out of print but has continued to be well received over several editions. We are hoping to re-publish it with a new end-piece essay to acknowledge the changes in context over the past decade.

These pieces are written in a similar style to the original small essays in the book – short, poetic and personal – and their content mirrors the concerns that Unpsychology has been addressing in the past decade. You can find the Series Introduction and first ‘chapter’ in this new series HERE.

Note: Since I wrote this piece - itself an update of a previous post – my own father died (at the end of September 2024). He was a very old man, not a far-too-young-to-die man like Greg Gilbert (the main subject of this piece) and his death was not unexpected, but his dying adds context to my reflection. I decided not to change the piece, to leave it as it is, but responded directly to my Dad’s death in my last post HERE and so it’s there in the background…

Soul Manifestos 2024

#05 : Love makes a mess of dying

A glimpse is all I can manage, like sun-hurt snow too tender for touch”. (Greg Gilbert, 2019)

I came across Greg Gilbert’s work when he was lead singer with Delays, a Southampton based indie band, somewhere in the mid-noughties. His voice was distinctive and beautiful, and the band made intelligent, moving pop music — including two albums, Faded Seaside Glamour and You See Colours, that I consider to be among of the best of the decade. After four albums with the band, Greg increasingly focussed on creating visual art as much as music. Then, in 2016, he received a diagnosis of stage 4 bowel cancer with secondary lung. He had two small daughters, and a fiercely loving and articulate partner, and their story is poignant and moving.

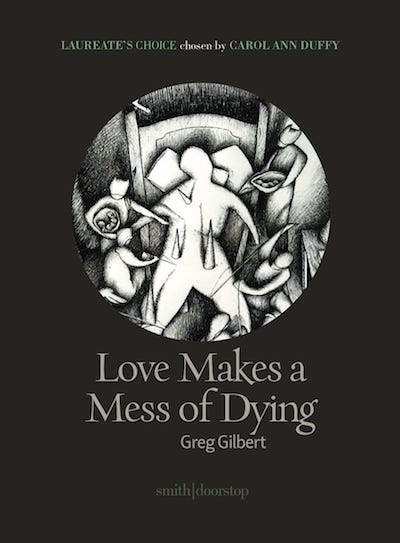

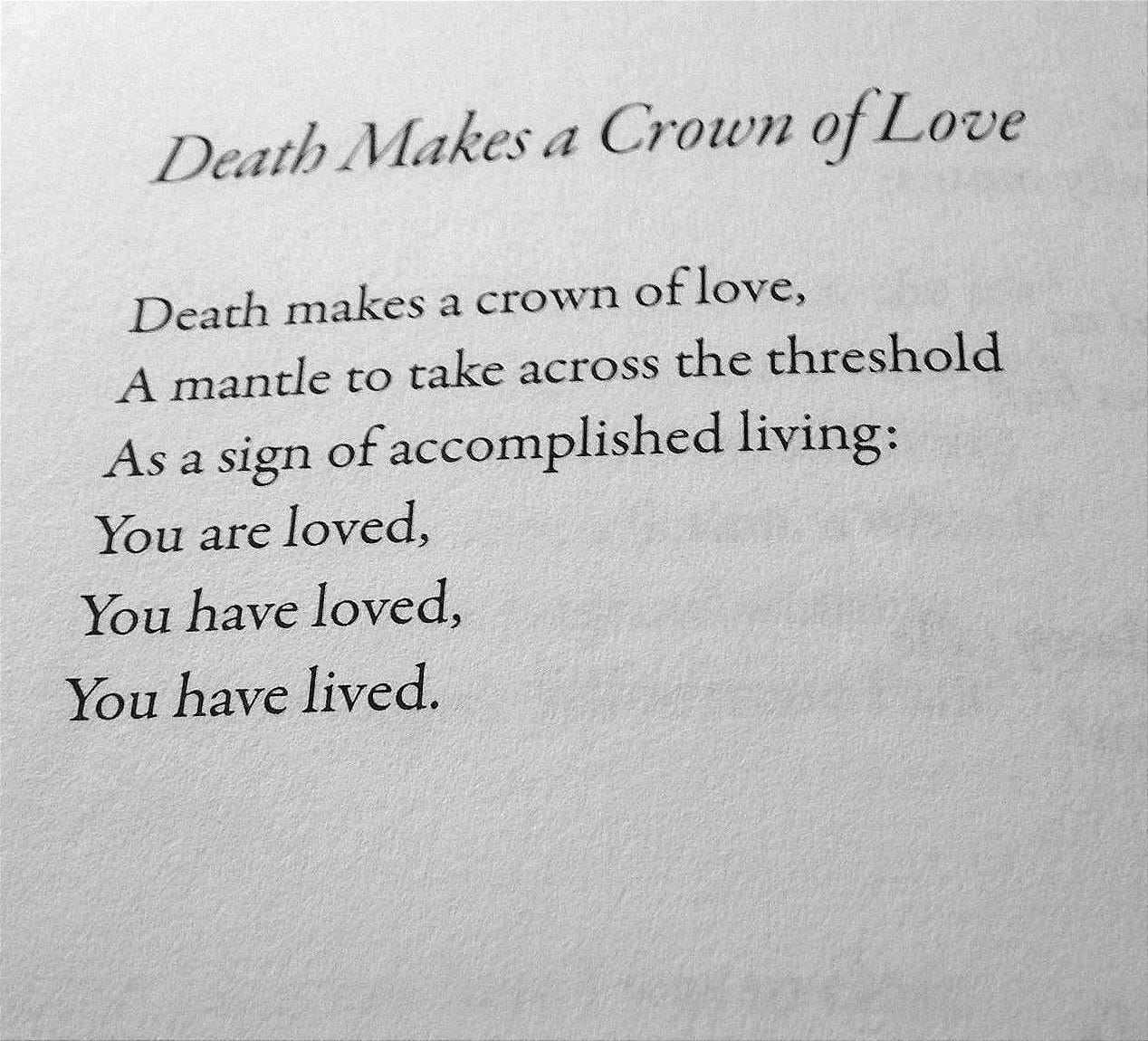

2019 saw a further creative chapter in Greg’s story with the publication of a pamphlet of his poetry, Love Makes a Mess of Dying,2 which is heartrending, truthful and beautiful. All through, he carried on painting and recording his experiences on social media, until his death on the 30th September 2021.

The reason I am writing about Greg is that, in his art and poetry, and through his life, he connected dying with love and pushed neither away. We all need to die, and wouldn’t it also be great if we could learn to die and grieve ‘wise’ (as Stephen Jenkinson might say) bringing together the lessons of life with the inevitability of death — both for us humans as individuals and as cultural, collective beings?

However, things don’t tie up nicely, and Greg’s story didn’t just finish when he died. He left a grieving family – including his brother, Aaron, who was also his best friend and collaborator in the Delays. Greg died a public death – not in a big, iconic way, but there was an outpouring of love and recognition for his life and art on social media and beyond from many people, who like myself, had followed his band and story.

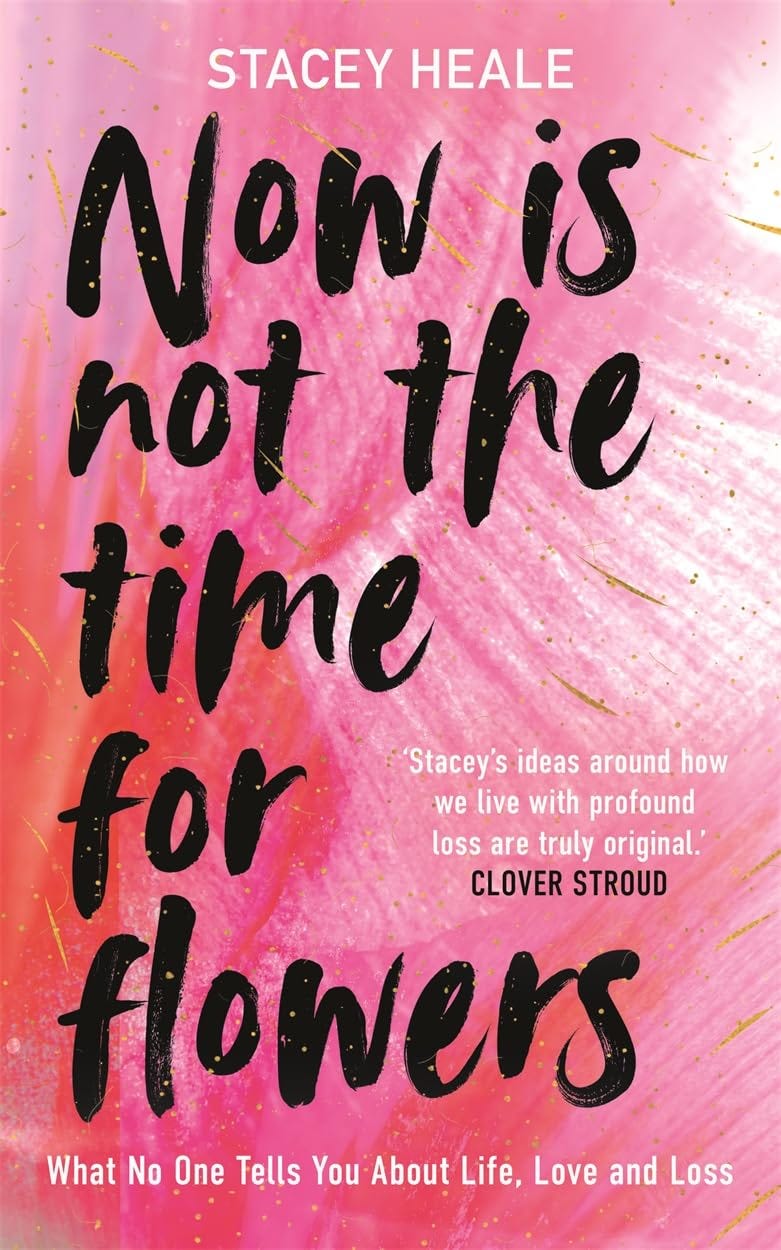

His wife, Stacey Heale, struggled massively with the loss, of course, but also with the double-binds and emotional knots, dead-ends and imbalances she found herself subject to. She has chronicled this journey over the past years on social media and now in her new book, Now is Not the Time for Flowers: What No One Tells You About Life, Love and Loss, published just a few months ago.

As Greg’s own book title said it, “love makes a mess of dying”, but dying also makes a mess of love, connection, expectation and obligation and all the realities that emerge starkly when the person who was dying, dies. It is often the people left behind who have to deal with the mess, of course, and we are forced to face death, in our own ways, whether we want to or not.

This imperative to face death isn’t a new concern. You might think we’d have got it right by now, this dying and grieving business, but, as Stephen Jenkinson points out, somewhere along the way, in this culture at least, we have become death-phobic: “It isn’t pain, after all that is unendurable. It isn’t living that is undoable. It is dying in a death-phobic time and place”. He goes on: “Death phobia…is not culture. It is anti-culture. It multiplies wherever culture is under attack, especially when it is failing from within”.

Greg Gilbert wasn’t immune to this fear - none of us who have grown up with this cultural phobia can be – but I think he tried to face it; to bring dying into the centre of the room. “I need to get my gods in order, they have grown unruly…”, he wrote; and, as if in reply, Stephen Jenkinson suggests: “Try it this way: What if your dying is an angel? And what if your dying job, should you choose to accept it, is to wrestle this angel of your dying instead of fighting it?”

As I was writing this, I found out that Stephen Jenkinson himself is now facing his own muscular angel. Having been writing, touring, teaching and speaking for years on the ways we can face death – individually and in our families and culture – he is ill and dying too, and faces the contradictions and challenges that this grounding truth brings. In a moving letter to his subscribers at the end of May 2024, he wrote:

“When someone tells you news that he/she has told five hundred before you, it comes across as barely news. It’s rote, and it’s your turn, and that’s it. Part of the disease-brief protocol I was told: “There’ll be good days, and bad days.” Which has turned out to be rigorously, unspectacularly, allopathically true.”

To hear that terminal illness is an ordinary, allopathic reality from someone who has been articulating his rigorous, unspectacular spiritual truths for many years is somehow comforting. He is not reaching for miracles, but recognises that to simply practise – in the form of blessings and love sent virtually and in person – has merit and is to be welcomed.

I do wonder whether he still thinks about wrestling the angel – it feels a very energetic thing to do when physical energy is at such a premium! If so, then such an act might involve a recognition that grief is something we all can do – together – whether we are the person dying or one of those around them as they die. Grief is there within us as we prepare to lose someone, and also if we are the person who is to be ‘lost’. Grief is the sharp reminder that might be important to to stay in the room; to stay with the love and the pain:

“Whatever tricks I tell myself to deaden before dying — That I’m alone, that alone is the essential state — comes Undone at the sight of love and I’m afraid, not of dying, But of leaving a mess for love.”

(Greg Gilbert, 2019).

Soul Manifestos and Pieces of Joy written by Steve Thorp and illustrated by Ruth Thorp is a collection of small, poetic essays written against the backdrop of conflict in modern culture, politics, economics, ecology and psychology. The small manifestos are written for wonder, wisdom, joy, love, and openness - and for the common good. They describe an alternative and grounded response to the material world, a way in which we might live our lives with depth and soul. It was first published in 2014 by Raw Mixture Publishing.

From the Poetry Business website: https://poetrybusiness.co.uk/product-category/books-pamphlets/laureates-choice/: “In May 2019 The Poetry Business published The Laureate’s Choice Anthology to mark the culmination of Carol Ann Duffy’s decade long tenure as Poet Laureate. The anthology includes a selection of the best poems across the series, showcasing the voices that Carol Ann has discovered and celebrated”. Love Makes a Mess of Dying by Greg Gilbert was one of these pamphlets. It’s a book I love, and reminder of a man whose creativity was undying, even as he wrestled with angels and with love.

Thanks Steve for another interesting exploration here. I wonder about this term 'mess'. Is it possible perhaps that love appears chaotic, as we humans have little way other than to fall, and to fail under its principal. And that death is the foremost teacher in this field?