Introduction

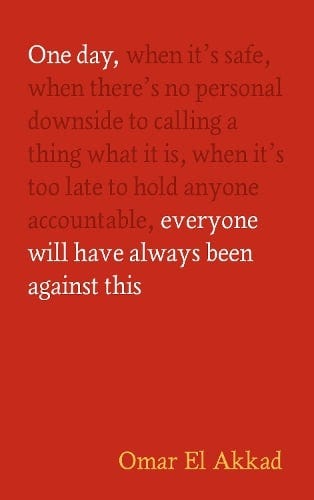

One day, when it’s safe, when there’s no personal downside to calling a thing what it is, when it’s too late to hold anyone accountable, everyone will have always been against this*

*These lines (the subtitle and longer quote above) are from the front/title page of Omar El Akkad’s 2025 book. It’s an amazing and harrowing read. It speaks truth in a way that is unusual, honest and stark. This piece is about this book, but not only about it. It is about Gaza, and climate breakdown and the growth of authoritarianism, but not just about them either.

I think the one thing I want to say about all of these interlocking crises is that they have been coming down the road together for a long time. There have been no specific ‘starting points’ for ecocide, genocide, Holocaust, fascism and other horrors. They do, however, all have their consequences, and these are crises of mind as well as political, ecological and humanitarian ones.

This is unpsychology, I guess…

Note: all the images in this piece are by Hosny Salah, a Palestinian photographer currently living in Palestine Gaza Strip. Hosny also works with Artists for Gaza and you can find that organisation at https://artistsforgaza.org.uk/hosny-salah, where you can also make a donation, or purchase Hosny Salah’s work. Alternatively you can make a donation to Hosny on Pixabay to support his work HERE.1

Avoidance is visceral

A couple of months ago I bought a book that had been recommended on Instagram by the DJ and broadcaster, Nihal Arthanayake. It’s called One day, everyone will have always been against this by Omar El Akkad. It’s about a world in which everything is crumbling. It’s about Gaza, and genocide, and being an immigrant, and climate breakdown, but most of all its about the kind of double standards that pass for ‘normal’ and ‘civilised’ in a global culture dominated by liberal Western norms, and how this means that horrors are ignored and enabled – and often not even named.

It’s not a comfortable read, and not, as some people have intimated, because it calls out ‘Zionism’ or takes a stand on Gaza, or apologises for or enables terrorism. It is uncomfortable because he reveals, in beautiful, poetic and precisely journalistic prose, the utter hypocrisy embedded in the Western liberal order. It’s almost an upending of all that we, living in the democratic West, have accepted and assumed as ‘normal’.

I bought it, then avoided reading it for a little while. It’s not that I’m averse to reading about the ravages of Empire and capitalism, nor am I unaware of the brutality inflicted on millions of people, and the Earth itself in the name of so-called ‘freedom’, and so-called ‘democratic values’, and so called ‘capitalism’. My avoidance was because I knew that this little book would take me to the heart of the matter, and ask me to not pass over the brutal consequences of this through-the-looking-glass world we’re living in: the ‘mirror world’ (as Naomi Klein names it).

However, my avoidance feels viscerally uncomfortable – embodied, even. As I read this book, and others like it, my body tries to preemptively calm itself in the face of the horrors I read. Omar El Akkad is a journalist, but he’s also a novelist, and I am a practised reader of fiction, so it would be easy for me to compartmentalise what he is saying in the genre marked ‘story’. But this story is real.

As I was reading it, news came of the deaths of nine of the ten children of a Gazan paediatrician, killed when the IDF bombed the building they slept in. Today, as I am posting this piece, I read that her husband, also a doctor and also caught in the bombing, has died of his injuries. I almost couldn’t hear or read about that one. My self-calming body started its calming. My mind and body started to turn away. Yet, when we, who live in a Western liberal world, in which we have privilege and our culture is dominant, turn away, calm ourselves, numb ourselves with our visceral avoidance, we are in step with those whose more considered, deliberate avoidance will someday break our world completely.

(un)Psychology

The premise of unpsychology is that mind is contextual. And ecological. And lots of other things too, but let’s stick to contextual for the moment. In psychotherapy, we (psychotherapists) work with individuals – sometimes groups. The focus is usually the individual’s distress, dysfunction, development. The contexts are family, identity, experience. They might be cultural. They are seldom civilisational.

During my years as a therapist, I have worked with some people whose ‘trouble’ was centred on the ungraspable hyperobjects of climate and ecological breakdown. I have had people crying with me over burning tar sands, the plight of an injured bird, the desperation of climate change, the tick tick tick countdown to something catastrophic that they see coming and feel helpless to prevent. Often their anger and despair was at the wider political and economic contexts and with the people who were in positions to make decisions and make changes, but who refused and/or were too tied into transactional politics and commercial interests to do so.

These things, literally, drive people mad. Injustice. Unfairness. Cruelty. And they fear the consequences of the accumulation of all these troubles for themselves, their families and the wider community of humans and non-humans who live in the world. The problem with psychology is that, however contextual it can be (and it often is), it seldom goes beyond the diagnosis and the treatment of the individual in the consulting room or surgery.

Meanwhile, there are bigger connected troubles:

all this context is tied up with what goes on in people’s minds and we all experience it differently; making our own personal and communal stories that might come from the mainstream, or from the counter-culture. Regardless, this forms itself as a belief system and often, at a cultural level, as propaganda;

however much therapy we have, drugs we take, or self improvement and mindfulness programmes we enrol on, the world is still breaking. Bombs are still falling on Gaza; the world is still warming to catastrophic levels; politically polarities still grow as we tip into fascism and what Richard Seymour calls Disaster Nationalism;

this propaganda and breaking come together and they overwhelm us. We move into avoidance - not as a pathological, psychological thing, but as a survival mode. Those of us who are privileged enough (liberal Westerners) can just about cope with this. Those who bore and bear the brunt of historical and contemporary colonialism find it increasing difficult to survive and fend off the generational and personal trauma.

So, although One Day… isn’t ostensibly a psychological book, it is an unpsychological one, in that it sets out starkly the ways in which these propagandised systems work, tying us all in, and creating the through-the-looking-glass world we live in, with all the subsequent psychological consequences. And for many the consequences are also physically and often mortally violent.

Mortal violence

Mortal violence, I would like to think most people would agree, is to be avoided. However, something in the cultural propaganda and psychological normalisation of liberal (and increasingly nationalist) cultures puts a limit on such values, on empathy, and when violence might be ‘justified’ or ‘allowed’. These limits are always based on who is judged (or claims) to have the right to inflict violence, and in whose name and cause.

However some questions are sometimes too viscerally uncomfortable to consider:

How many deaths are too many? One? A hundred thousand?

Does it matter if these dead bodies are children. Women? Men?

Does it matter that they are brown bodies?…

…Or the bodies of those regarded as ‘other’ by those who set boundaries and borders?…

…Or the bodies of those designated as terrorists?

And if these were white Western bodies, in their tens of thousands, what then?…

Of course, I am just asking questions…

I’m aware that pacifism these days is largely regarded as a naive and impractical position to take. I am also fully aware that circumstances might unfold that might change such a position. I can understand how peaceful people who were attacked might turn to supporting violence in a defensive mode, or in solidarity with others who are being attacked.

These questions are deeply uncomfortable. After all, aren’t we democratic liberals who consider all people ‘equal’? Maybe. But shouldn’t we be asking those who don’t feel included about this? Those who are regarded as ‘barbarians’, as Louisa Yousfi – also a journalist – puts it in her equally uncomfortable and eloquent book, In Defence of Barbarism: Non-Whites Against the Empire:

“The truth is, we’re suffocating. Here’s what happens. There’s a long history of domesticating barbarians. In the language of the Empire, this is called integration.”

Both Yousfi and El Akkad point out that belonging is always conditional. Integration is always a one-way ticket. It has its roots in Empire and colonialism and in questions about who has the right to judge who ‘belongs’, who ‘owns’, who is ‘acceptable’. Those who are not acceptable are ‘barbarians’ – uncivilised – not allowed to determine their own nation-hood; subservient to the claims of other determined nations; refused asylum; denied entry. Bombed indiscriminately in their neighbourhoods and camps. Subject to genocide.

And ‘barbarians’ who inflict violence or take revenge are ‘terrorists’. Full stop.

Walking away

In the more hopeful part of his book, Omar El Akkad wonders what it might take for us (by which he means an undivided solidarity of ‘us’) to challenge or even walk away from all this. The systems we all live within, and which oppress and destroy humans and the world alike, are regarded as ‘normal’, ‘civilised’ – inevitable. Yet we can still choose to walk away – to refuse to accept and live with the so-called civilised requirements of this world in the mirror.

We can choose to see the deaths of thousands of people, and the degradation of our planet as things that are far worse than the inconveniences that might emerge from direct action and activism. Worse than viewpoints labelled as ‘outrageous’ by those who claim to be outraged by such uncivilised behaviours that they claim ‘enable terrorism’. Even if the action itself is a bit of paint splashed on a building, or a march of thousands waving Palestinian flags, or boycotting companies investing in Big Oil, Israel or malevolent state actors and governments.

Somehow such activism is regarded as beyond the pale. The deaths of thousands of children, meanwhile, are regrettable, even awful, but calling for ceasefires and boycotts are acts of moral naivety - even extremism.

These are ‘reversals’…

As Louisa Yousfi points out: “It’s like imagining the bodies of white children washed up on Mediterranean beaches – another reversal of perspective that lays the world bare.”

Meanwhile, Omar El Akkad’ writes: “Everywhere there is a great rage simmering, boiling over and everything feels like an argument. But there are no arguments to be had anymore”. His hope is in people refusing their complicity in the systems that create these reversals and mirror-world distortions. Walking away. Refusing to accept the story. Saying, “I will not be part of this”.

So, how can we walk away? We who are the liberals and moderates of the West? How do we square the circle of our embodied, psychological complicity in the atrocities that have been coming in waves since the early days of Empire? As I said, this is visceral, embodied, instinctive. It’s not about guilt, shame or blame, but nor will minimising truth or shedding responsibility make any of it go away. What will come, will come. There are no arguments to be had anymore…

All this is at the heart of unpsychology – the psychology that is not psychology. The recognition that ‘mind’ is part of ‘world’, which in turn has been infected and is being inexorably killed by the normative, viral justifications of colonialism and capitalism – and by the terrible visceral avoidances which allow us, as individuals, to turn away from the consequences of climate destruction, racism, genocide and other horrors.

We might ‘flinch’, but then we turn back again to our ‘normal’ lives.

Conversely, though, could we ‘flinch’, take a step in the other direction, and keep on walking?

The child of Omelas

A short story by Ursula K LeGuin has always haunted me.

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas invites us to imagine a world – a happy city filled with wise, empathetic complex people – a kind of utopia. Of course, no one could describe the world we live in right now as utopian – the antonym, dystopian, would be more appropriate for what is unfolding! However, the essence of the horror we live with – in our case, the turning away, the justification of suffering with the pretence or hope that a kind of democratic, liberal, civilised world is still possible, if only we defend its ‘values’ – is also the shadow at the heart of LeGuin’s story.

You see, the happiness of the people of the city of Omelas depends on the suffering a single child. Everyone knows about them, as they cower in a dank basement, tortured, neglected and abused. People come and gawk at this pitiful creature, young people are brought to see them. These young visitors are expected to feel horror at the child’s existence and plight, but then to return to their lives. They are angry and grieving for a while, but then they gradually recover to live happy, civilised and free. In fact, the civilisation itself depends on the knowledge they have of this single, suffering child hidden somewhere out of sight, deep in the city.

But, LeGuin writes, “there is one more thing to tell, and this is quite incredible.”

“At times one of the adolescent girls or boys who go see the child does not go home to weep or rage, does not, in fact, go home at all. Sometimes also a man or a woman much older falls silent for a day or two, then leaves home. These people go out into the street, and walk down the street alone. They keep walking, and walk straight out of the city of Omelas, through the beautiful gates. They keep walking across the farmlands of Omelas. Each one goes alone, youth or girl, man or woman.

Night falls; the traveler must pass down village streets, between the houses with yellow- lit windows, and on out into the darkness of the fields. Each alone, they go west or north, towards the mountains. They go on. They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.”

These lines have haunted me for years. Whenever I read them, that visceral avoidance that sometimes helps me to get through a day in which there is grief in every news report, horror in every video, dissipates just a little. It softens. And I wonder whether I can also walk away and wonder what this might mean. And if we keep wondering, I realise, then this might be part of what keeps hope alive.

Throughout Omar El Akkad’s book, there are the presence and ghosts of human children. His own childhood. The children killed in Gaza and many other conflicts and genocides in recent history. And his own daughter. He writes about when she was one and a half and fell ill with a respiratory condition. During the days she was in hospital he was “the most scared I have ever been”. Every parent can relate to that, I imagine. Every grandparent. The thing we fear the most is the death of a child, and Akkad sums up the contradiction in this eloquently: “I don’t know how to make a person care for someone other than their own. Some days I can’t even do it myself”.

That’s the challenge we face, isn’t it, those of us who do try to care? To know and trust that my love for my daughters and granddaughters when they were small (and I experienced a similar night of deep fear when my own daughter had measles at a similar age) is infinitely powerful, but also carries the key of a door to a greater empathy, the courage to find our own ways to walk away and connect with the wider solidarity that this carries and implies.

Last lines

Last lines in books and stories can be life changing. The lines from Ursula K LeGuin’s Omelas tale definitely were (for me at least), and those in El Akkad’s beautiful, elegant and horrifying book are too. It’s rare to find someone able to walk through illusion and disenchantment, accommodation and disillusion; rejection, anger and despair, and yet find themselves writing these “clear, clean lines” (as LeGuin put it) that lift us into another future that humans may be able to conjure. Not a perfect place, nor even a particular safe or happy one, but one in which we can see things as they really are:

“It’s not so hard to believe, even during the worst of things, that courage is the more potent contagion. That there are more invested in solidarity than annihilation. That just as it has always been possible to look away, it is always possible to stop looking away. None of this evil was ever necessary. Some carriages are gilded and others lacquered in blood, but the same engine pulls us all. We dismantle it now, build another thing entirely, or we hurtle towards the cliff, safe in the certainty that when the time comes, we’ll learn to lay tracks on air”

Note: the images in the piece are by Hosny Salah, a Palestinian photographer currently living in Palestine Gaza Strip. Hosny also works with Artists for Gaza and you can find that organisation at https://artistsforgaza.org.uk/hosny-salah, where you can also make a donation, or purchase Hosny Salah’s work. Alternatively you can make a donation to Hosny on Pixabay to support his work.

So much stirs in me from reading this Steve. I dimly perceive the possibility that an honest reckoning of our complicity in the horrors we see unfolding need not lead us into debilitating guilt, but rather towards transformation - through moral courage. In his critique of contemporary christianity, Richard Rohr suggests that the liberal west maintains its distance from horrors 'out there' through a 'cult of innocence' (a cultivation of an image of blamelessness). The Latin word 'innocens' means un-wounded. So to adhere to this notion of innocence is to deny our own wounding. Everything changes, it seems to me, when we frame what we witness through the understanding of our own woundedness. The tragedy of modern psychotherapy is that in most cases it is not truly psycho-logical - that is, it does not track 'symptoms' back to the deepest layers of our wounding, what we might call suffering at the level of 'soul' (a realm of being in which we are all fundamentally in this together).

I want to walk away; I don't know how to; I want it to all go away; I want to assuage my guilt and be one of _the good ones_; I want to retreat; I want to open up, be courageous, take holy risks; I want to curl up and numb reality out.

I don't know what to do. I am beginning, slowly, to see what it is like just to keep the wound open. To see if anything grows there of its own accord. This stuff is hard. I know it's not harder than living in a warzone, under occupation. But it's hard.