A note from Alexander Beiner

One of my struggles in life is biting off more than I can chew. Usually, I manage to swallow, then sigh with relief that I didn’t choke on my own curiosity. Recently I’ve been immersed in a story that piqued my interest, but I wasn’t sure I could digest.

It all began a few weeks ago when historian Benjamin Breen’s book Tripping on Utopia was published. It explores the birth of psychedelic science after the second world war, and argues that two unlikely figures influenced its formation: Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. From the book’s blurb:

“Far from the repressed traditionalists they are often painted as, the generation that survived the second World War emerged with a profoundly ambitious sense of social experimentation. In the '40s and '50s, transformative drugs rapidly entered mainstream culture, where they were not only legal, but openly celebrated. …at the center of this revolution were the pioneering anthropologists--and star-crossed lovers--Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson.

Convinced the world was headed toward certain disaster, Mead and Bateson made it their life's mission to reshape humanity through a new science of consciousness expansion, but soon found themselves at odds with the government bodies who funded their work, whose intentions were less than pure. Mead and Bateson's partnership unlocks an untold chapter in the history of the twentieth century, linking drug researchers with CIA agents, outsider sexologists, and the founders of the Information Age.”

Shortly after Tripping on Utopia came out, Nora Bateson was the guest teacher on my course New Ways of Knowing. Nora is Gregory’s daughter and President of the International Bateson Institute (IBI). During a break in the session, she explained that she and her colleagues at the Bateson Idea Group disagree strongly with the way Breen has framed Bateson’s life and work (the IBI is a group of lifelong Bateson scholars that direct the 501c3 for Bateson’s literary rights and archival restoration, of which Nora is a board member). There is no doubt that Bateson was involved in psychedelics in the 1950’s, but the position of the Bateson family and other Bateson archivists is that Tripping on Utopia presents a sensationalised image of Gregory Bateson.

Nora wanted to write a piece on it, and a couple of days earlier I had announced that this Substack was open to guest writers. The timing and the themes seemed perfect; psychedelic science, systems change, polarisation and a breakdown in sensemaking, combined with scintillating hints of clandestine conspiracies.

I felt it was essential to include Breen in the conversation so he could have the right of reply, and we made contact. As drafts of the piece went back and forth, and Breen sent his rebuttals to the critiques I relayed, I found myself mediating between two opposing perspectives and buried in the tangles of history.

I read Tripping on Utopia in a weekend, and the next week read pages of audio transcripts from the 1940’s that the Bateson Idea Group provided. I poured over interviews with Bateson describing his LSD experiences, watched footage from the time and waited as people trawled through archives half-way across the world. As the days passed, I felt a growing tension in my body as different truths competed around me.

It was increasingly hard to hold both the propositional layer of ‘what happened’ and the deeper layers of human feeling that cried out ‘what matters’. I was between people who strongly disagreed, and who all seemed to feel the keen pain of being misrepresented. I wanted to find the ‘win-win-win’ for all sides, but facts were inextricably tangled with perspective and emotion (as they often are) so it was complex. I kept moving between ‘editor’ and ‘mediator’ and ‘human’, the boundaries of my roles blurring as contexts shifted, and my understanding of that process deepening as I learned more about Gregory Bateson’s work.

In short, it’s been kind of a trip.

It was an intense process for everyone involved, and it’s one that would ultimately lead Nora to write the kind of insightful and beautiful prose I associate with her work. She decided to set aside a critique of Tripping on Utopia, and instead she’s written a heart-felt and fascinating explanation of why Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson’s ideas are so important for the times we live in today. It feels like a generative outcome, because as Breen told me, the issue of Mead and Bateson’s overall centrality in psychedelic history is open to interpretation, as most things are in the study of history. That interpretation could go on forever.

For those interested in the details, Breen published an article on his Substack, which includes a detailed rebuttal to the Bateson Idea Group’s critiques. Nora has expressed that, “A rebuttal to a rebuttal is an unending rabbit hole of bickering about old documents,” and has written a piece that she hopes will take the conversation somewhere new.

Communication is Sacred by Nora Bateson

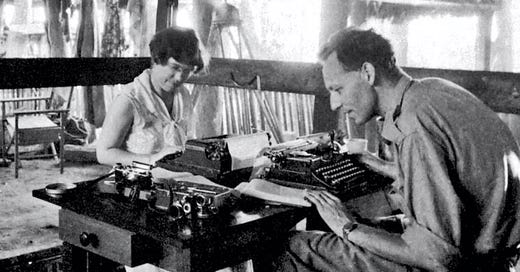

When Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead met in 1932 in New Guinea, the world was gearing up for a war against fascism. The problems with confronting fascist ideas have not changed since then. The trap of trying to confront fascism is that it grows stronger with polarity, and the problem with not confronting fascism is that it grows stronger when it is not met with resistance.

So, what can be done? Rallying against a group that believes themselves to be superior further ignites a sense of righteousness to their polarity. But without counteraction the momentum of the hateful cause grows deeper and wider into communities, demanding more loyalty, and more exclusion.

Most attempts to stop fascism seem only to generate it. These ideas and the work that began back in the 30s in response to Nazism are relevant today in response to the escalation of divisive algorithms currently careening societies into authoritarian tech nightmares.

A New Science

Bateson began to ask how fascism takes hold of societies and what might make it more difficult for those kinds of ideas to find purchase. He began what would be a lifetime of work addressing the thinking that was susceptible to fascist ideas and how to meet this sticky problem. One of his observations is that when any aspect of a living system is torn from its contextual relationships, it can then be exploited. How a description is made of a person, a family, a community, a culture, or an ecosystem –matters.

Does the description hold the complexity, or does the description sever the relational connections? The more relational, contextual understanding there is, the less likely polarities are to take over. Thus began the work to create a scientific inquiry that would study how systems are entangled. These became systemic, cybernetic, complexity and chaos theories. This new science, he hoped, would bring contextual information where reductionism had left gaping holes in the knowledge of culture, society, family, health, and ecology. All of these share a vital sphere of communication and relationship.

As living organisms, we commune. As living organisms, we perceive contextually.

But what is the communication? And what context has been perceived to commune within? If the communication is divisive, and the context is one that favors the control of machines over the wilderness of life, the very core of membership with each other and the living world is eroded.

The way people, societies, cultures, and any other living systems are described reveals the labels and other abstractions that serve divisive agendas. How much context has been brought to the description? How much complexity?

We all know what it feels like to be misunderstood, or categorized in a way that does not hold our whole selves. When people pick one context of someone’s life as their identifying characteristic, the complexity of the person who is being described is violated. I am my DNA, but I am more than that, I am a mother, but I am more than that, I am my job, but I am more than that, I am my nationality, but I am more than that, I am my generation, but I am more than that, I am my body, but I am more than that. I am my religion, but I am more than that. Even if someone’s description of me could hold an accurate illustration of all of that, it would be incorrect, because I am not the same from one day to the next. I learn, I change.

To take all the contexts of someone’s life into account in a single description is probably impossible, except perhaps through poetry or art, which allow for an unending shifting of perception. Describing another person or even describing oneself in a way that includes the complexity of life requires another sort of expression that comes from another set of assumptions.

What is communicated in decontextualized ways get recontextualized into other stories. I may have been in the vicinity of a farm, but that does not make me a farmer. Or, I may have known someone who knew about a crime, but that does not mean I knew. Taking out of context one small slice of information and presenting it as a description of the person or community within other sets of stories is an easy way to recontextualize them. This sort of characterization distorts perceptions and impressions.

Schismogenesis

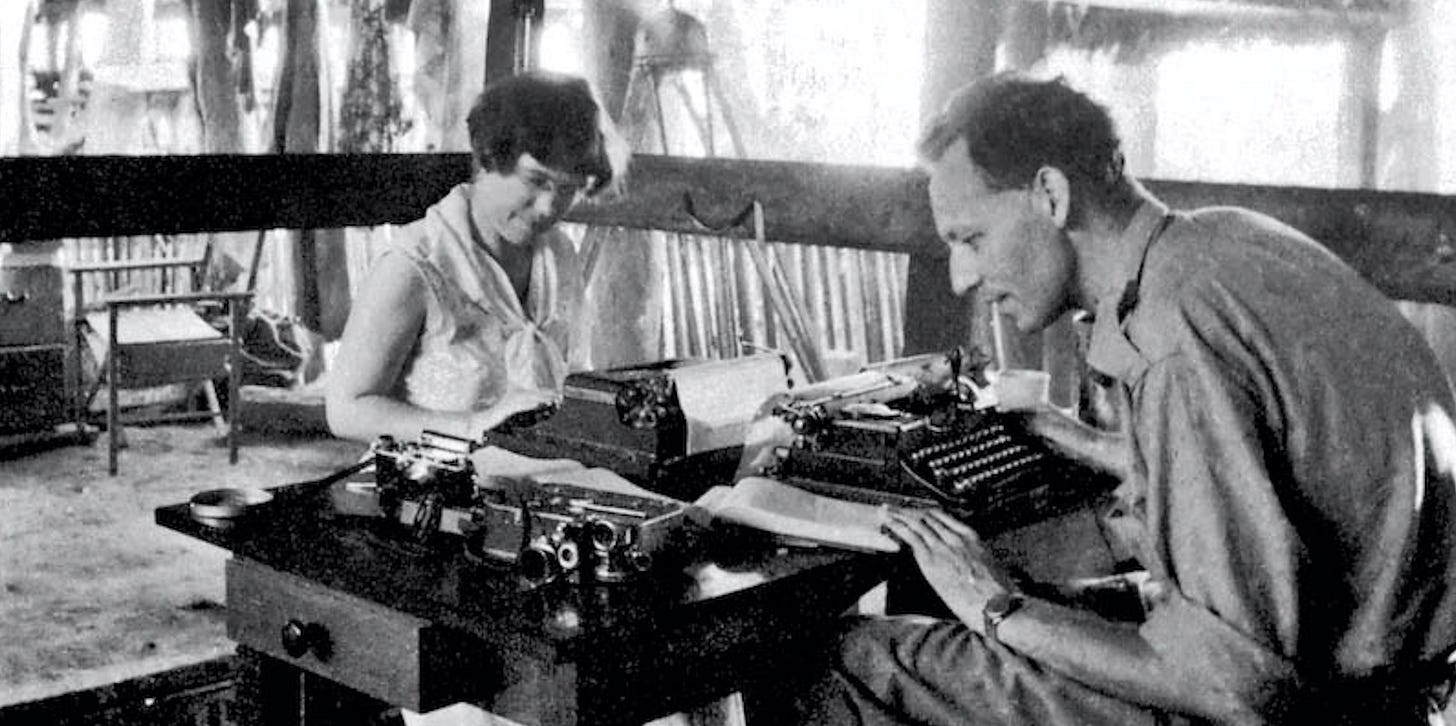

Gregory’s eagerness to fight fascism led him to work with the Office of Strategic Services during WW2. The OSS used his knowledge of culture and communication to confuse the enemy troops.

In the summer of 1943, like many anthropologists, Bateson went to work in Washington, D.C., for the Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.) as a "psycho-logical planner.'' That office dispatched him to Southeast Asia, where he spent twenty months in Ceylon, India, Burma, and China. By his own accounts, he accomplished very little. The one activity which caught his interest, however, was operating a radio station aimed at undermining Japanese propaganda in Burma and Thailand. Studying its content, Bateson had translators engaging in small-scale symmetrical schismogenesis. "We listened to the enemy's nonsense, and we professed to be a Japanese official station. Every day we simply exaggerated what the enemy was telling people." Upon his return to New York, he gave Geoffrey Gorer the impression of being "very disturbed with the O.S.S. treatment of the natives. I think he felt that he was associated with a dishonest outfit." Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist by David Lipset, p. 174.

This technique of exaggerating and omitting information distorted the communication. For example, Gregory would intercept a message that might say, “The enemy is 37 kilometers away,” and change it a little: “The enemy is 6 kilometers away.” The immediate effect of tweaking this message is that the troops get ready hours early. But that is only the beginning. The disorientation of the communication has a knock-on effect of rotting the trust and relationships necessary between soldiers who fight and live together. This is what Gregory referred to as “schismogenesis.”

This may be one of the most relevant and useful ideas for anyone interested in the runaway disintegration of socio-cultural communication.

The word schismogensis means creation of breaking; as a communication pattern, it creates a generator function of communication that breaks communication. The confusion creates confusion, leads people to the next wrong question, and froths up distractions. Where an ecological system generates relationships that make more relationship, schismogenesis escalates relationships that break relationships. Today, divisive communication is eroding relationships and potential relationships everywhere. Even though this may seem like a trivial trick to most people, for Gregory, it was a deeply cynical act.

For Gregory, deliberately messing up communication between people is and was a violence that reaches beyond the bounds of war. It is a violence to the sacred act of communication itself. Of course, Gregory justified it during the war as something that needed to be done for all the right reasons (to fight fascism). There is a family rumor (this is not recorded anywhere that I know of) that shortly after the war, Gregory's despair after this experience was so deep that he tried to take his own life. His attempt failed. And he spent the rest of his life tending to and in respect of communication.

Communication is not what is said or even what is not said. Communication is what is received in the context. Additionally, communication is not what is on the transcript; it is what it was possible to say or not say. As living creatures, our perception is made up of combining bits of stimuli. We put notes together to form songs, we combine light to form colors, we combine context and words to form verbal and nonverbal communication, and we combine gesture, culture… it’s how perception happens. Communication is much more than words. It’s gesture, symbol, silence and so much more.

Manipulating the combining of different pieces of communication to fragment it is a violation of life. Gregory ached with that knowing. Decades later, this is the core of my work on Warm Data and the rigor necessary to perceive information as alive.

How Does Change Happen?

But try… just try… to explain to the media or write a scintillating book about the importance of interdependent systemic life! Much of today’s media will reject the warmth and aliveness of contextual description; there is not enough bite, not enough sting, and too many sides. The media likes a two-sided controversy, a basic polarity. The stories that hold our families and ecosystems in danger now have thousands of sides. The grave dangers of our time will not fit in binaries. But since the audience of the press is captivated by controversy, decontextualizing is justified; it sells. And in doing so, the ability to perceive the most basic form of life—relational interdependence—is suddenly an abstract intellectualization.

This is how you break the relationships that integrate a living system. Once broken the parts of the system appear to be separable, controllable. However, the attempt to control eventually has the inverse effect, along with innumerable other consequences.

Given this understanding that "control" is at best an illusion and at worst a devastating violence to living systems, the question that Bateson was asking is: How does change happen? How does a family change? How does a marriage change? How does an ecosystem change? How does a culture change?

An understanding of living systems reveals that change cannot be produced through linear control- so how does one participate in the processes that produce systemic change?

This is a critical moment in the history of humanity to be asking that question. There have been many models of change and theories of change, and yet, those things that one might wish would have changed by now have not. Wars, corruption, destruction, the makings of the polycrisis are still very much as they were, only worse.

Gregory Bateson tried long ago to shift the habituated way of thinking about change as something linear. But the mechanistic dream of life being fixable in the way that a machine is fixable has proved to be a difficult dream to wake up from. Finally, after almost 100 years, it may be possible to begin approaching this question of change differently. Gregory's work, in particular, is just now beginning to be recognized.

How do you think about change if not in linear strategies? You tend to the relationships.

All living and social systems are vitalized through their relational ecologies. When the relationships shift, the whole structure of the surrounding relationships also shifts.

How do you tend to the relationship? Relationships are made of communication, even at the cellular level of your body, all the way up to global politics. So, if you want to shift the conditions of the relationship, you tend to the communication.

This is not about making a new script or vocabulary. It is about contextual and transcontextual shifts. Ecologies move in inter-relational ways — Bateson said this 80 years ago, and his father, William Bateson, said it in 1888. Indigenous cultures have been saying this for thousands of years.

Gregory was frustrated at how difficult this idea was to bring into a world of mechanistic habits. He died in 1980 feeling that his work was not understood. He was largely correct, cultural and economic assumptions are still stuck in un-ecological thinking. There is still little comprehension of how communication and relationship ripple into consequences untold.

Twisted Communication

Why? You may notice that this messing around with communication is a basic characteristic of daily life. Every advertisement is doing it. Algorithms, entertainment programs, politicians, news outlets—everyone is manipulating what can be perceived. The practice of twisting up communication is so prevalent it may even seem normal.

So why does it matter? It matters because interrupting, tweaking, lying, exaggerating, silencing, omitting—these little acts become huge fissures in our relationships. This practice dehumanizes, devitalizes, and shreds our deep connections to each other. The delicacy of life on this planet is hanging in the balance.

It happens at home, in our communities, and in the world around us. The infection of this breaking of our together-unity is tearing the fibers of life apart in the way cancer cells tear apart the body’s ability to communicate. It makes the world a place where the only reasonable thing to do is "watch out for number one."

While it may be a prevailing logic of debating or convincing of others of our position, the art of communication distortion is a dangerous game. It leads to a moment much like the present, when it is impossible to know who is sincere, and what information they base their sincerity upon. Who should you believe? What is left of our communing that is not for sale? A sentence is likely to be worded to evoke particular impressions. A montage of images can conjure a particular notion.

What would happen if there were a common recognition of communication as sacred; if it were not used as an instrument of control?

Of course, there will be mistakes and misunderstandings in communication. Some mistakes are extraordinarily painful, some are funny, some are confusing. This is different than strategically manipulating. But I wonder how easy it is to tell the difference in a world that is so accustomed to communication distortion as a methodology of everyday navigation through relationships in the workplace, school, home, and technology. I wonder if it is possible to find a way to allow communication to untangle from the pain, and the profit of the last 3000 years. “Everything you say, can and will be used against you.”

Using communication to achieve a goal is likely going to backfire in unexpected ways. Communication is always entangled in many more processes of being alive than just speaking. The agenda may be clear, but the way it ripples out is not predictable.

Combining Contexts

I released a film about my father in 2011, after years of research and editing. That project pushed me to examine again and again my own limitations in creating a description of someone else’s life, in this case, my father’s. I knew I could not put every second of available footage in the film, nor could I account for the contexts around each of the decisions he made in his life. I am not certain that he could even do that if he were alive to try. I realized that in making a description of his life I was describing my relationship to his life.

Again, this is a combining of my experiences and my perceptions with my own forms of communication. It is fair to ask if the film I made about him is really about him at all? I could have included gossipy assumptions about who he slept with or highlighted his most epic successes and failures. It would have been a more traditional biopic if I had. But I found that tweaking of the information-- exaggerating and omitting— made the story into something that did not give the audience practice in perception of complexity.

I found that shifting the blur of uncertain events into crystalized assessments of another agenda was like cutting him to pieces and reconfiguring him into someone I did not even recognize. The same schismogenesis that broke Gregory’s heart is created in exactly this way. And yet, by not employing those techniques, the film was difficult to get into broad distribution. What this tells me is that the fast food of polarized gossipy reductionism is seductive and lucrative.

This misuse of one of the most precious aspects of being alive is ubiquitous. Our children are growing into a severely fragmented world, our bodies are showing the illnesses of disconnection, and our communities are divided. Politics and technology are merging into an alarming communication horror story with AI to categorize us all into our algorithms and pit us against one another on social media.

Communication is the birthright of living organisms to make combinations, contrasts, and generate relationships. To climb a mountain is to combine the body's balance, muscles, temperatures, and breath with the circumstances of the hike. Is it a date? Or are you running from a bear? We combine information beyond our verbal words. We combine impressions, we combine memories… this is how living things make sense of the world.

It has always been important to be careful with communication, not to use it to twist or spin or augment … but lawyers, marketers, advertising agencies, politicians, academics, pharmaceutical research, religious leaders, media professionals and military strategists have been perfecting the art of manipulation of perception for so long some say it's 'human nature.’

The Thirty-Six Strategems by Sun-tsu/ Zhuge-liang laid out methods for psychological warfare thousands of years before anyone ever imagined the CIA. Cambridge Analytica's manipulations of algorithms, and the mishap of news stories that cash in on controversy reveal a collective selling-out of the sacred tenure of communing.

There are some things that should not be for sale. Beyond global politics and business, beyond our personal insults, beyond the place where "you are wrong, and I am right".... the revolution now is to honor a more alive world of relationships, and in doing so to honor life. Communication matters, both verbal and non-verbal. Sit by a fire side by side, sing, hold babies, walk slowly as you assist the elders, grow, cook, and eat beautiful food together.

The need to create time for analog human to human communication cannot be underestimated now. There will be no community without first communing.

Alfred Korzybski said: “Thus we are living in a delusional world, a world of phantom semantic structures.” The structures of language go on to structure our lives--not only in words, but in the world the words describe and in the way we sit in silence together.

To support more guest posts like this and help The Bigger Picture grow, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.